Phasing out PFAS use

In recent years, the U.S. has seen a surge in policies to address PFAS—a class of chemicals known as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down in the environment. Over the last eight years, states have increasingly adopted policies restricting PFAS, and those actions—in conjunction with at least 30 percent of retailers recently evaluated committing to eliminating PFAS in key product sectors —have contributed to a reduction of PFAS in the marketplace. However, states recognize the ongoing need for action.

PFAS Uses and Health Concerns

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a class of nearly 15,000 chemicals used to make products like cookware, food packaging, carpets, clothing, and firefighting foams. They are also used in industrial processes and are often discharged into waterways.

Research has linked PFAS exposure to various health problems including weakened immune function, cancer, increased cholesterol levels, pregnancy-related hypertension, liver damage, reduced fertility, and thyroid disease. As evidence of how toxic these chemicals can be, in 2024 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized drinking water standards for several PFAS chemicals at levels as low as 4 parts per trillion.

Nearly all U.S. residents have PFAS in their bodies, with studies detecting these chemicals in blood, breast milk, umbilical cord blood, placenta, and other tissues.

Expected PFAS Policy and Regulations

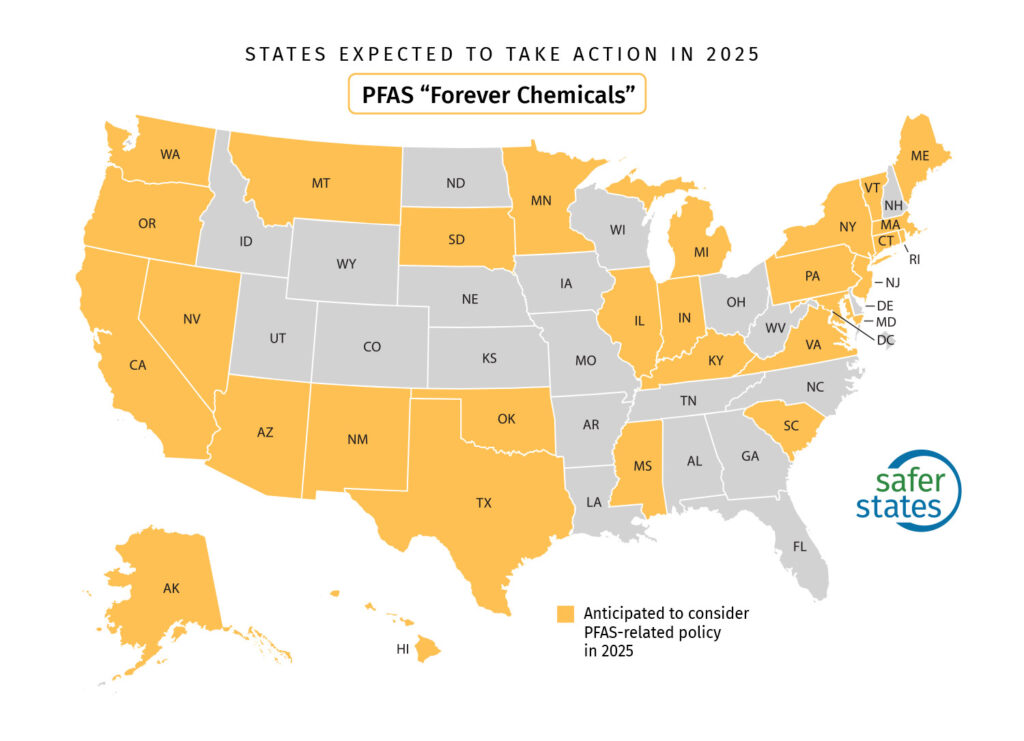

This year at least 29 states will likely consider policies to address the PFAS crisis, ranging from eliminating their use in products to limiting the spreading of PFAS-containing sludge on farmland and setting water standards. These states include Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.